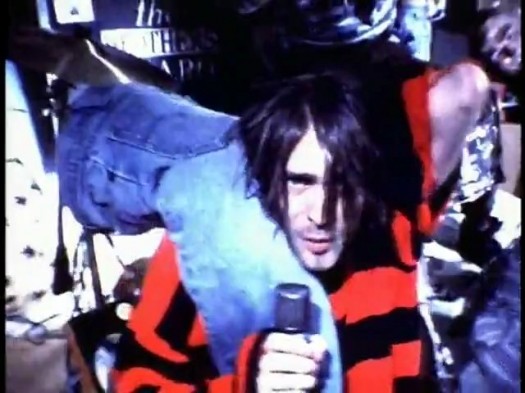

R&RHOF REPOST – Don’t Know What It Means: Talking With The Director of Nirvana’s “Come As You Are” “In Bloom” and “Sliver” Videos

[This article originally ran on September 14, 2012)

Like most music fans, we at THE GOLDEN AGE OF MUSIC VIDEO are casting our memories back to 1991, when Nirvana’s landmark Nevermind album pulled the underground into the light and reset the pop music landscape on alternative terms. Right in the middle of it was director Kevin Kerslake, whose musicianship and indie sensibility helped establish him as an insightful music video director who infuse a sense of personal integrity into his work; each of Kerslake’s videos seems to be trying to accept the mission of ringing true with the audience by showing the artist’s indelible mark or fingerprint — a sample of their creative DNA if you will. The list of artists he has shot clips for reads like a roll call of nonconformity: Sonic Youth, Faith No More, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Nirvana and more.

Having been close friends with the late Kurt Cobain, Kerslake spoke somewhat guardedly about his experience shooting the videos for Nevermind’s “Come As You Are” and “In Bloom” as well as Incesticide‘s “Sliver,” clips that helped cement the legacy of Nirvana in the history of music video.

It seems like when you came to work with somebody like Nirvana or even Red Hot Chili Peppers, these are all guys who started independently, doing things their own way, making music on their own terms, and you seem to be the sort of go-to filmmaker who understands that aesthetic because that’s very much a part of how you are as well. Is that fair?

Yeah, yeah. I mean, I think that, at different times, bands like that go to people because they – who don’t necessarily think along those same lines because they want to be more commercial — don’t have that gene, so they’ll pick somebody who does, but I guess my own personal approach is maybe because I came at it through music, or I played music myself, my own personal connection with music has compelled me to do something that sort of honors the song or the band aesthetic or something that is inherently part of who the band is. See, I think the commercial gene is just something that I just – I never really consider it. If you start anticipating what people will like and you start to create sort of things with those expectations — you create the idea for a video or shooting in such a way — then it just feels like sort of your center of gravity is off in a way, and I start to mess with the weight of something that is a little more meaningful, as somebody who’s tasked with making something. I can’t remember who it was and I’m sure a lot of people have said it actually but every time you pick up the camera you want to save the world, or every time you pick up a brush you want to basically bottle up everything into a single stroke, and in the same way, it’s difficult to speak of a commercial medium in those sorts of terms, but because of the bands I was doing and who they were, it just felt like we weren’t necessarily doing something commercial. We were doing something that just meant a lot more than just selling records.

Some of the directors I’ve talked to who shot videos in the late 70s, early 80s, when there was no MTV yet, they said it was like the lunatics were running the asylum. You could just about do anything you wanted and nobody really paid attention to music videos so much, but then it turned into an industry.

Yeah, but the thing about that phase, “the lunatics running the asylum” phase, is that that is seen through the eyes of the record industry. It’s the same thing when you go back to the period that’s the heyday of American cinema in the 70s, late 60s and 70s, the Easy Riders Raging Bull phase, right? And they said the same thing, and the industry perspective was like “we had to wrest control from these maniacs,” and the fact of the matter is, there was so much passion in the industry at that time to make videos that really meant something and in the same way, the music world – that was like a renaissance, basically. Obviously, technology in terms of MTV and the music videos flourished as a medium in a lot of different ways, but I think that at the same time, indie rock and even popular rock and hip-hop came a little later, but the seeds of it were starting to be seen. There was so much amazing music that was going on at the time, and it wasn’t necessarily commercial ventures. It was just there was a lot of fire and creation, and people were making amazing work in so many different mediums, so if you break down “the lunatics running the asylum,” it’s like yeah, and now they did wrest control of it away and there are different milestones along the way, but Nirvana was really the first one that I had to contend with because it was the type of genre of music that I was doing at that time, that I had been doing for many years, so all of a sudden the suits started to come to the set —

When did you first have a run-in like that?

I did “Come As You Are”, which was the second single of Nevermind, and it was almost black and white in terms of that change, or night and day…

Was it during “Come as You Are” that they started getting on in your face?

It was in the process of doing the video. I had a different relationship with Kurt, so we had like more of a one-on-one connection, but you could see how the suits came to smell money and start to act in ways that were much more along the lines of how we know the music industry to operate.

For “Come As You Are,” I believe you said in the past that the set was supposed to look like a Hollywood mansion with holes in the walls, and a lot of it was about Kurt having to deal with new found fame and the record company. Is that close to what you were trying to do?

Yeah, well, there’s a lot of stuff that’s been said about it. I can’t talk too much about them just because of the situation, but Kurt didn’t want to be in the video. They were sick of themselves on magazine covers, and they said “we just don’t want to be in the video,” and that obviously wasn’t going to happen (laughs) so I had to come up with a way that you satisfied the clowns and you satisfied Kurt and the band, which was basically just this device that obscured them a bit which was just the water, or shooting through a stream of water.

That looks like a massive set.

It’s not as big as it looks on camera (laughs). Movie magic.

Ah, yes, movie magic. The next video, “In Bloom”, really spotlights their sense of humor, so, did you come up with the idea for it to be a performance on a fictional black-and-white television show?

Well, we were just talking about the Ed Sullivan Show, I believe. And that’s it. You can’t get too deep on it.

Sure. And then you shot “Sliver”, which is a little claustrophobic and has much more of an indie sensibility than the others.

Well, it’s Super-8 and it’s shot Kurt’s basement basically…

There you go, perfect. Did you get any push back from the suits when you brought in a video shot on Super-8, or were they looking at you and the band and thinking “these guys are not going to listen to us, we just have to deal with them”?

I mean, this was for Incesticide [a compilation of early Nirvana songs] so “Sliver” was an old single. Actually, I heard that before Nevermind actually. For “Sliver,” I don’t think there was a lot of attention on that, label attention that is, on what was going on. Also, I do a lot of Super-8 stuff. Mazzy Star’s “Fade Into You” was Super-8 and Smashing Pumpkins Cherub Rock was Super-8. I shot a lot of stuff on it.

What is it about Super-8 that you like?

It’s just cheap and pretty and it’s – a lot of the video cameras right now, they’re sort of the same – they offer the same sort of rewards in terms of you can go out on your own and just shoot without assistance, without a lot of light and it’s like a little – it’s just like an extension of yourself basically. Like even with “Sliver”, Kurt and I – I didn’t have an assistant. I shot that thing alone, and Kurt and I were moving stuff around his basement and we just did it ourselves basically, so I’m sort of a retard when it comes to loading cameras, and all that stuff so it’s nice to be able to be self-sufficient.

Take a look at the director’s videos for “Come As You Are” and “In Bloom”, as well as “Sliver”.