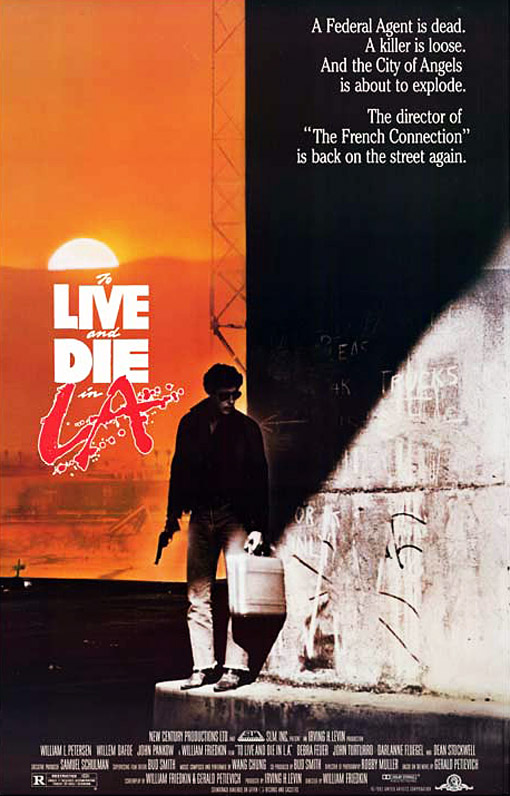

If You Like DRIVE: Jack Hues of Wang Chung Recalls Working On TO LIVE AND DIE IN L.A.

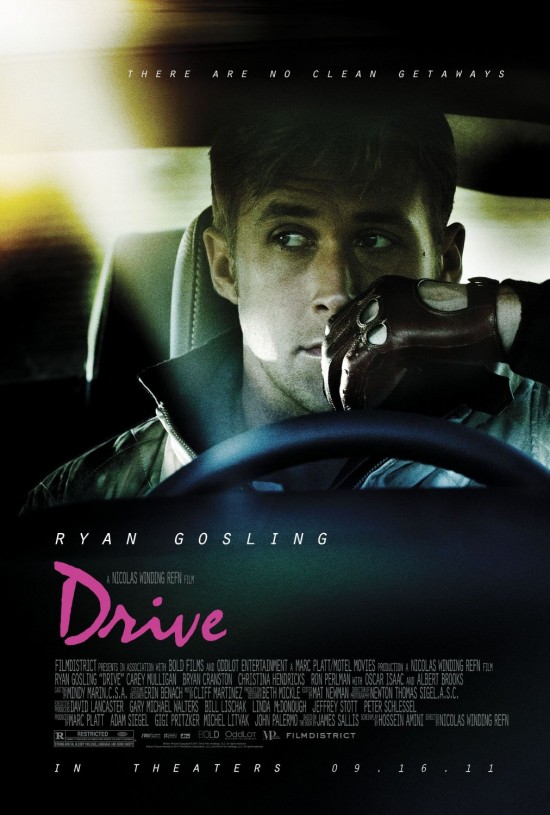

The new Ryan Gosling film Drive wears its 1980s film-style heart on its sleeve in several ways, from the noir-in-neon-light camerawork to the Tangerine Dream-style soundtrack – even the title font purposely replicates Risky Business. Filmmaker Nicolas Winding Refn constructed a gripping modern tale whose visual sense harkens back twenty-five years to L.A. films such as Michael Mann’s Manhunter and Thief as well as William Friedkin’s To Live and Die in L.A.

In a recent Elvis Mitchell interview, Refn named the Friedkin film as a specific influence, so THE GOLDEN AGE OF MUSIC VIDEO now brings you an interview with Jack Hues of Wang Chung, creator of the To Live And Die in L.A. soundtrack, as he recalls the process of creating that trademark soundtrack, the title song, and the accompanying music video.

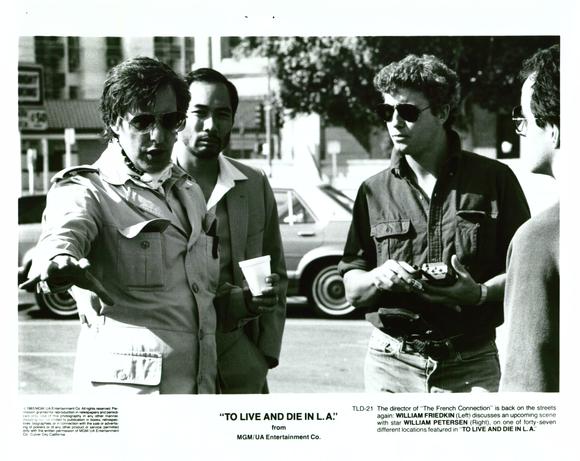

So, what you have done at this point, you had an MTV hit with “Dance Hall Days,” and you had a soundtrack hit with “Fire in the Twilight” [on The Breakfast Club soundtrack]. So, when we get to To Live and Die in L.A., it seems like a logical jump — a next step up, if you will. Did [director] William Friedkin come to you?

Yes, he had basically been using “Wait,” which is a track on Points on the Curve as a temp track while he was editing To Live and Die in L.A.. He was using it as music that was sort of associated with the visual atmospheres. He was using “Wait,” and I don’t know whether he was considering few more regular composers or whether we were his first,, but he called us up. I was in London at that time, and we were really working on the follow-up to Points on the Curve, and that wasn’t going well I have to say because I guess I’ve always been an artist who writes the next thing I write, I don’t think. So we were writing these sort of artsy whimsical Beatles-inspired sort of tracks, you know.

With your success so far, there was no sitting down now and feeling that things were different? It didn’t feel like that at all?

No. I mean, you’re not really doing that, you know, these games are played, and you’re not playing it. You have to wise up, basically. (laughs) And I was kind of not sure as to what I had to do, so it’s really quite a difficult time. And my sense, you know, I mean, you sort of talked about “Dance Hall Days” being an MTV hit, and The Breakfast Club song being the soundtrack hit, and doing a soundtrack like To Live and Die in L.A. as a sort of logical progression, but that progression was not apparent to me at the time, and certainly not to Geffen Records. Their sense was, “you had an ‘almost’ hit with ‘Dance Hall Days,’ and it was a Top 40 song because I think you got to #16, something like that, and it’s good, but now we need a number one record. We need a proper pop hit. Where is it?” (laughs) I mean, not to me personally because they would never say that to an artist. They’d say, “we love what you do, you just keep writing and that would be great,” but to our manager, they were giving him hell. So when Friedkin proposed us doing the soundtrack, my reaction was that this is something I’ve dreamed of doing because it’s an opportunity to fuse writing longform and harmonically complex music with pop music. Because of my training and the years as a pop musician, and then getting into classical music — those were the things that we need to bridge together. But Geffen were not into it, and at first, they would not let us do it. Their view was that this is a distraction from writing that Top 40 hit. So David Massey our manager had to fight really quite hard for them to go “okay” and they said we could have two weeks to do the project and that’s it. So that was how it was done, really. I mean, we didn’t see the movie, we didn’t come to America to do it, we just did it. We rented a studio in London and I remember just renting a load of equipment basically…

Wait, you didn’t see the movie?

No.

What did you know ABOUT the movie that informed the creation of the music?

Just speaking to Friedkin. I had this hour-long conversation with him, where we just sort of talked about what he was doing with the movie and we talked about “Wait”, and he basically sort of said “I want you and your band to go into the studio and write me an hour’s worth of music, just jam out. An hour’s worth of music that’s kind of lightweight, and I’ll cut it into the film.” Friedkin is a very interesting guy. As a director, he knows what he wants, you know, and he knows how to get it, and that bodes well, I think. And in that conversation, you know, I sort of downloaded what he wanted somehow, not through exactly what he said, just through the intention of the conversations. Maybe that’s taking things a little bit far, but I had this very clear sense of what it was that we needed to do, and I was writing a song that was kind of lightweight, “City of the Angels,” the instrumental track that sort of opens the main part of the film and the where the money is being printed and stuff. I was working on that. I’m trying to sort of condense it down into a song, and it became a fifty-minute kind of jazzy, proggy piece. So that’s how that turned out, and then sampling all the percussion instruments, gongs and bits of metal and stuff, you know, and that’s what provided some of the sounds in the track “Black, Blue, and White,” I think it’s called, and all of that. And a slow piano piece.

So it all just sort of evolved in its time, that sort of world of creativity. Billy sent over some videocassettes of rushes and prints which Nick [Feldman of Wang Chung] watched. I didn’t want to watch it because I thought that if I watch it, I might suddenly think that we’re doing the wrong thing, and that’s really going to put a spanner in the works, you know. So I just kept doing what I was doing, and Nick came in and said, “This is good. What we are doing is good.” And then we basically sent it off to Friedkin, and a couple of weeks he got back in touch and said, “It’s perfect. Absolutely brilliant. Come and see this!”

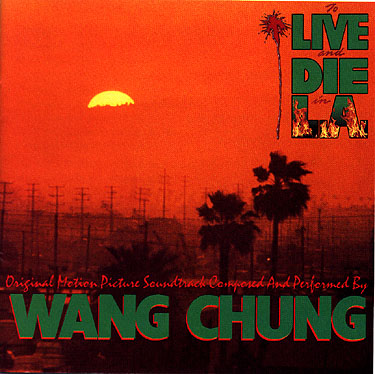

He flew us out first class — one of the rare first class flights we took to the U.S. (laughs) — and we got into this quite big sound studio. They were doing the mixing in a Los Angeles studio which Friedkin had a part ownership, and we sat down and the opening sequence at that time was a big bang, and the voices come in this crescendo, and visually there’s that style, it’s orange, with the palm trees in the storms, and then when the music started with the money printing, I mean, it all seemed perfect.

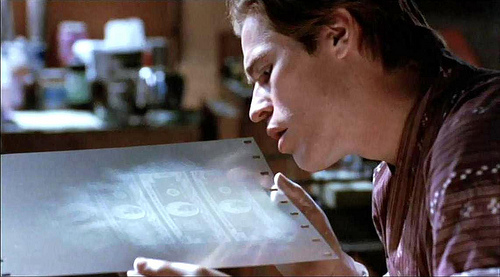

Willem Dafoe readies a counterfeit printing plate in the film

Willem Dafoe readies a counterfeit printing plate in the film

You know, I still find it amazing that the pace of the music was basically the same tempos with the money printing machines, and it was mind-blowing watching it. It’s probably one of the most exciting things I’ve ever experienced in my career as it were. I was thrilled, and I think at that time, there was this sense that “this film is going to be amazing, you know, with very interesting young actors like Willem Dafoe and William Peterson, John Turturro,’ so I got back to the U.K, and I felt I had to write a song, a title song. Friedkin had said to me in that initial conversation that he didn’t want me to write a song called “To Live and Die in L.A.”, that he wanted a soundtrack. And he was quite specific about that. So I sort of wrote the song, and I find that when you are working with talented people, do the opposite of what they say. (laughs) It’s a good way to go.

Really?

Like when I worked with Tony Banks [of Genesis]. I wrote some lyrics for him, and he said “I don’t really like that. I want it be more like that.” And I’d keep going and he would be “oh, actually that’s good.” (laughs) So, yes, I sent this song off to Billy, and he said, “Brilliant! I’ll re-shoot,” and he basically re-shot this front section, you know, so they have this prelude so they can have that song in there, you know.

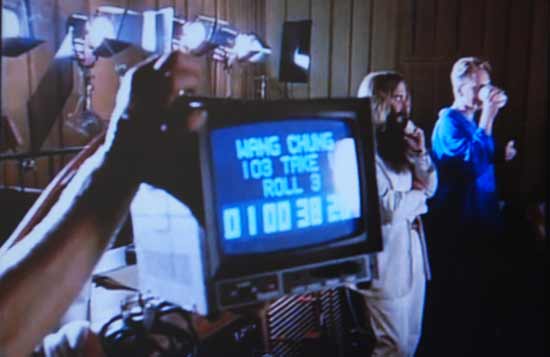

And then you guys shot the video for the song?

Yes, that’s right. He said, “I want to do a video,” and at the end of the day it felt like the whole thing got a bit out of control. (laughs) It’s beautifully filmed, yeah. I mean, Nick and I aren’t actors, so when we have to sort of do these little reaction shots, something like that, it makes me really cringe. But nevertheless, it’s beautifully shot.

Jack Hues and Nick Feldman in an “acting” moment from the “To Live and Die in L.A.” music video

Wang Chung with filmmaker William Friedkin in the music video

another shot from the music video (that’s recording industry legend John Kalodner next to Jack Hues)

It was great to work with Billy, and it’s quite an interesting little insight into who was around of that time, like John [Kalodner] and he was really great and mentoring us and guiding us, treating us with kindness at that time. The video is the general sense of it — it’s kind of like that experience. The video is like a movie — it looks nothing like that truth, but it’s kind of the truth. (laughs)

*******************************************************************************************

Fans of Drive should definitely check out To Live and Die in L.A., as well as the soundtrack. Keep up with the band at http://WangChung.com, as well as in the videos below.

To Live and Die in L.A. music video

To Live and Die in L.A. movie trailer

Drive movie trailer

Drive Soundtrack