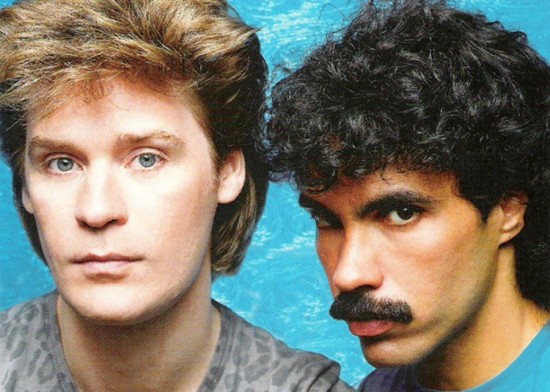

John Oates Talks Hall & Oates Music Videos, Back-To-Back Nights At The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame & The Cutting Room, And His Solo CD Compilation GOOD ROAD TO FOLLOW

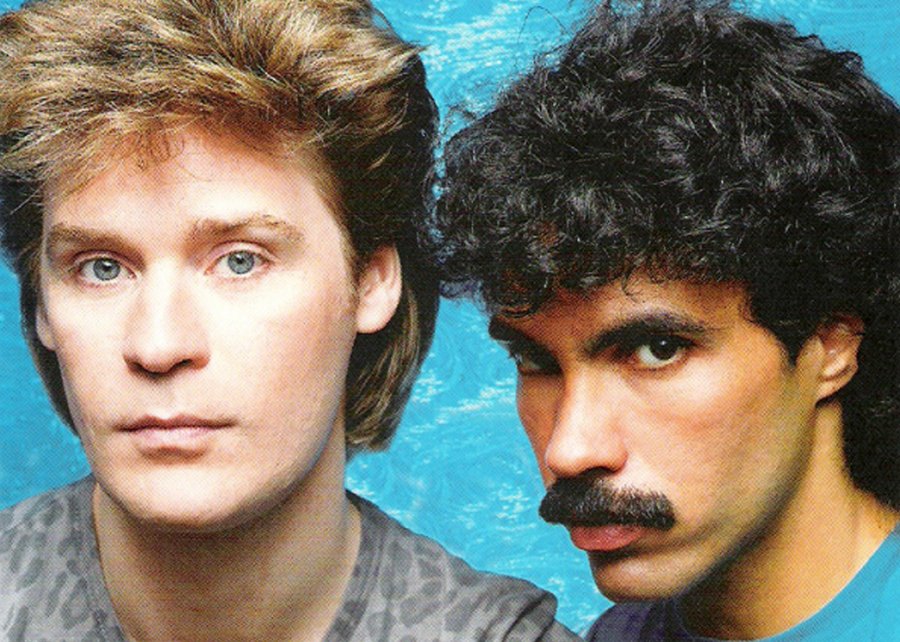

Daryl Hall and John Oates have the best problem they could possibly have. They have too many hit songs to fit into one concert. As the number-one selling duo in music history, they have delivered their popular brand of “rock and soul” for over 40 years, scoring six number-one hits and 34 appearances on the Billboard Hot 100. Hall & Oates, the once uncool and now strangely cool, are basking in the glow of their imminent induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn on April 10th (following by John’s solo gig at the Cutting Room in NYC the next night). John Oates spoke with us about the upcoming ceremony, his recently released solo singles compilation, and their highly derided (especially by John) music videos.

Let’s talk about Good Road to Follow. This three-CD collection of your independently released download singles is great. This compilation gives people a chance to absorb them all in one package. It goes back to what you did when you were growing up.

Yes. Full circle I guess.

You collaborated a lot for this album. What were some of the highlights?

Every one of the collaborations has been a highlight in its own way. I don’t rank people in order of importance or talent. Everyone brings something unique and unusual and exciting to the table. Regardless of whether it’s a beginning songwriter who brings their energy and enthusiasm, or a grizzled veteran who brings a lot of experience and perhaps some wisdom, it was an opportunity to enter into people’s worlds and see how they create, think and operate. In the collaborative process, whether it’s writing or producing or in the trenches making a recording, it serves as an insight into people’s personalities – what moves them emotionally, physically, whatever. And that’s what it’s really all about. I thought it would be a cool thing to do to try the single approach, and it was very good in terms of awareness and press, but the reality is that I kind of shot myself in the foot because I released too many songs. The songs came out about once every month, and that was too frequent. It took a while for people to latch onto the fact that I was doing it, so by the time they were on the song that was released, another one was coming. It kind of backfired on itself in that regard, but I think compiling them into a physical album, or a digital album that you can download, it gives people an overview of how expansive this project has been, and how exciting it has been for me to work with all these people.

“Lose It In Louisiana” has some great swampy imagery, but how does a boy from Philly identify with Louisiana? I know that you’ve long admired Southern bluesmen like Mississippi John Hurt and Sonny Terry, but how did this song come about?

A few years back I did a solo album called Mississippi Mile, and there were only a few original things on it, but it was an homage to the music that I loved as a kid. I loved delta blues, I love the early days of rock and roll, Chuck Berry, the Memphis sound, things like that. When I started looking at all that stuff, I realized that Louisiana was the birthplace of this music, in a way. It was a heart that sent the blood up the Mississippi, and that music migrated north up into urban areas and eventually became urban R&B, so it seems to me that it all usually traces back to Louisiana. That song was actually written with a guy named Craig Wiseman. He’s well known for his country hits. He’s had numerous number one records. At our writing session, he had basically come back from a bender in New Orleans, and I was kind of hungover from going out with some friends the night before, so we pooled our post-drunken resources, and that’s where the song came from.

How was it collaborating with Kevin Griffin of Better Than Ezra on “Bad Bad Love”?

Kevin and I met at a BMI songwriters event. I think it was in Minneapolis, and I immediately gravitated toward his personality. He’s really outgoing and funny, he was really engaging with the audience, and of course I know his music as well. Basically – and this is how it happened with a lot of the people I’ve worked with on these songs – when I felt a spark, I would just reach out to them, tell them that I’m doing a series of singles, it won’t take much time, I just want a day out of your life, let’s have some fun, it’s on my dime, and let’s see what happens. The worst thing that can happen is that we have a great afternoon. He took the bait and said that it sounded like a great idea, so it was just a matter of schedule. He lives outside of Nashville and I’ve got a place in Nashville. He’s got a little work studio out in the country, and we sat around and started talking, which is how it starts in most of these collaborations. A conversation, basically light, get-to-know-you conversation, that we as songwriters are able to craft into a song. We got on the subject of people who get into bad relationships, like people who, when things are going well, make something go wrong for whatever deep seeded reason they may have. And that’s where “Bad Bad Love” came from. It was Kevin’s idea to do the “whoo hoo” hook.

He loves the falsetto, doesn’t he?

That was a really cool hooky thing that he came up with.

Have you spent much time in the South over the course of your forty-something year career of writing and touring?

We’ve been all over. If you want to talk about the Gulf Coast, we’ve played from the Florida panhandle all the way through Mobile, Gulfport, and out to New Orleans. In the early days, way before “She’s Gone”, in the early seventies, we became popular in Louisiana. We used to play all the state colleges in Shreveport, Nachitoches, Houma — we were all over the place down there, and we would spend a lot of time there. I’m a huge fan of the Nevilles and Dr. John and Allen Toussaint. For some reason, I have an affinity for that part of the country. It’s the music that makes the connection.

Congratulations to you and Daryl on your upcoming induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. There’s a real diversity of inductees this year: Kiss, Peter Gabriel, Nirvana. What does it mean to you personally?

I think of it as a lifetime achievement award. We’ve been eligible since 1997, so it’s not like this came out of the blue. I assumed that one day it would happen, but I wasn’t losing any sleep over it, but now it’s happened and it’s going to be exciting. It’ll be interesting to see how the drama plays out among all the artists, depending on who is there. Daryl and I aren’t going to have any drama. We just finished a tour, and we tour all the time. We’re getting along really well. We’re out there working, touring all the time. So for us, we’ll get up and play a couple of songs, accept an award, and we’ll see where the speech takes me in the moment. I’m trying not to think about it too much. It’s going to be quite an evening with 15,000 people in a giant basketball arena.

You brought up an interesting point about drama in a band. Sometimes duos experience conflict, but it results in great music. I know that you and Daryl have good time and bad times, just because that happens in a 40 plus year relationship. In your songwriting, has conflict between you ever helped or has it always been detrimental?

Daryl and I have never really had any conflict. We’ve had creative disagreements, but when we’ve done that, sometimes we just take a pass on the situation. For example, one of us will say, “hey, we should record this,” and the other says, “eh, I’m not feeling it”, or vice versa. Or we would be open-minded enough to say, “okay, let’s give it a try, and if it comes out good, then great, and if it doesn’t, we’ll move on.” And that’s how we’ve kind of done it over the years. We’ve never really ever had any major disagreements. When we have had a disagreement, we’ve just gone our separate ways, let it die on the vine, and then get back together. As we have gotten older, we’ve appreciated much more of the other’s individual personality and contributions, and I think I have a better appreciation of the body of work that we were able to create. I look back now and really wonder how the heck we did it. It’s pretty crazy. And we go and play these shows and people call out all these songs, and we have a catalog of over 500 songs. It’s mind blowing that we actually survived and did that. The hits are the hits and they are ubiquitous, but I think it’s the album tracks that we’ve created that are so interesting and unique and adventurous. In a way, I’m more proud of the work on the album cuts than I am of the hits themselves.

We know we’ll hear the hits, but are there a few album tracks you’ve pulled in over the last few tours that you’ll pull out for upcoming tour dates?

We actually go out of our way to pull out a few deep album cuts for the show. Our biggest problem is that we just have to many hits, and I don’t say that in a weird way, but as an honest fact! People come to hear the hits, and we have to respect that in our live performance, and we do that. We play the songs that people want to hear, but we insert songs, like from the Abandoned Luncheonette album, even song from No Goodbyes, which was an odd compilation that Atlantic Records put together after we left that label and went to RCA. We’ll do songs from Along The Red Ledge. We play songs that we think show the depth and breadth of where we are coming from as musicians. It’s not easy to do, so we have to rotate those tracks, and that’s fun for the band, because we can’t eliminate “Sara’s Smile” or “Maneater” or “I Can’t Go For That” or “You Make My Dreams” and all the other ones.

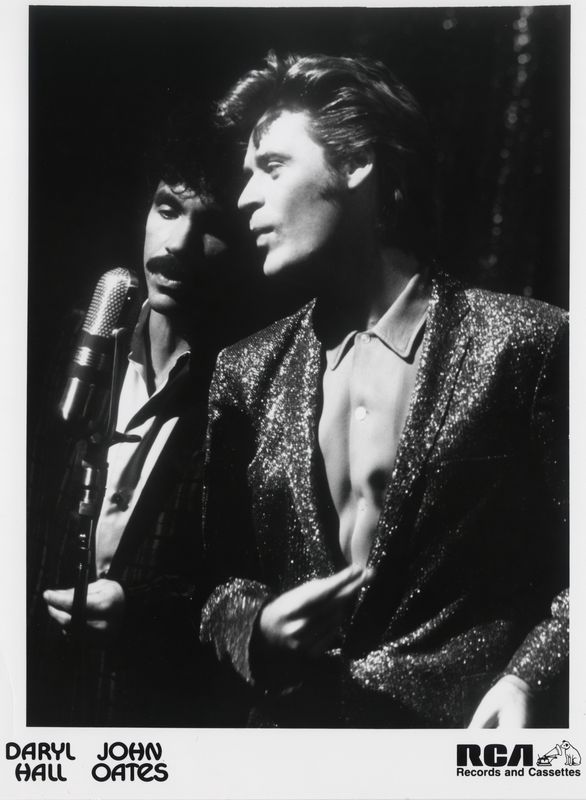

Let’s talk about the music videos, an area that has never really sat well with you. Over the years, you’ve indicated your disdain for the Hall & Oates music videos. The songs were just great for starters, and most of the music video directors who spoke with me said that it’s always easier to make a good video for a good song than a good video for a bad song. I think it’s a tribute to your talent – you and Daryl are such great songwriters that these videos couldn’t kill those songs’ chances to make it to the top of the charts.

That’s funny! Thanks.

In fact, there’s a YouTube video of you on a 1984 New Music Seminar panel, talking about how you don’t like that people in the music video era expect you to be an actor as well as a musician.

That New Music Seminar – was that the one where I was sitting next to Madonna?

Yes!

You know, I’ll never forget that, because that was a moment. I spoke the truth from my point of view, and you have to remember that I’d been recording for over twelve years, and Madonna was still on her first record [Her second album Like A Virgin was released later that year]. So, interestingly enough, I said what I said because I felt that way, and I still feel that way. She got on me about it like I was a dinosaur and didn’t realize the power of the medium, and she was one hundred percent right, because for her, the video presentation was as equally important as her music, because that is what made her who she was. To this day, she is still doing the exact same thing. From her point of view, she was right, and from my point of view, I was right. It was very interesting moment, where the beginning of a new generation was colliding with an older one.

James Brown was on the panel too.

He was?!

She cut him off and said that kids worship the television now. I think to speak to what you have said, Madonna needed the videos, and the videos didn’t give you and Daryl a career, the songs did.

Her videos were part and parcel of her recordings. It was all the same thing for her, and I get that. For me, it was an amazing opportunity to expand our awareness, and I just looked at it like a giant TV ad.

What do you remember from shooting “Private Eyes” with director Jay Dubin?

We had been rehearsing for our tour at SIR studios in New York. We rehearsed long into the night. We took a break around midnight, and Jay Dubin and the guys came in. Our tour bus was literally parked in front of SIR, idling and ready to go, and they were packing up our equipment. Jay Dubin and these guys came in with a pipe setup and a black curtain to drape over it. And we were literally saying, “Alright, let’s just do this and get out of here.” Someone had bought trench coats and fedoras, and we put them on over the clothes we were wearing. They set up the cameras, and we just jumped around. T-Bone Wolk [longtime Hall & Oates bassist] had just started with the band, and he’d never been in a music video before. He asked me, “What do I do?” I said, “Don’t do anything. Stand in one place, and every once in a while, turn your head.” If you look at the video closely, you’ll see that he actually doesn’t do anything except turn his head to the side once in a while. We just jumped around, and got out of there as quickly as we could.

What about “Adult Education” with director Tim Pope?

Big mistake. That was a mistake from the beginning. That was stupid. He was an English director, he wanted to make some sort of post-apocalyptic New York — we had nothing to do with that video. Quite honestly, we were so busy traveling and touring and they were demanding a video, so we kind of let that one slide, saying, “We don’t have any time to think about this.” We did have input with our other videos, but on this one, we had absolutely no input. They picked this director based on some other videos he had done, and they said to us, “We got it all together, don’t worry about it, it will be wild and amazing,” and we went, “Alright, whatever.” We literally showed up at the shoot and saw this enormous post-apocalyptic New York set, all these extras with torn clothes and crazy shit, and we just went along for the ride. But as we were doing it, we were thinking, this is really stupid. That’s one of the dumbest things we’ve ever done.

What about the videos directed by Mick Haggerty and CD Taylor, such as “Maneater” and “Family Man”?

Those Mick Haggerty videos were really good. Mick Haggerty was a real visionary. He was a great graphic artist. The “Family Man” video was very cool. I think the “Maneater” one is cool, with the leopard. The leopard got loose during the shoot, and jumped up into the rafters. We had to clear the building for an hour while the trainers tried to bring him back down. It was pretty crazy. They were all shot in L.A., and I think the quality is better in L.A., you had access to big time film studios, so it was just better.

How about “Out of Touch” and “Method of Modern Love” with director Jeff Stein?

That was the Baroque era, the Rococo era of music videos.

Rococo?

That’s a French word meaning a very fancy and elaborate painting. That’s when we were spending way too much money for no reason at all, and Jeff was great, but he was trippy and wanted to do something outrageous. He came up with all the ideas, like the drum rolling over us and peeling us off the floor, and the last shot in that video was Daryl and me in that giant bass drum, and they had to seal us into it. It was 3 o’clock in the morning, and it was super hot and clammy and stale. It felt like there was no air inside this bass drum. We were in there for what seemed like hours, and it was just the weirdest thing. We were looking at each other between takes saying, “So this is what it’s all come to! We are at the top of the pop music world, and we’re sealed inside a bass drum at 3 o’clock in the morning in a warehouse in Queens.”

You were front and center as lead singer for the “Possession Obsession” music video, directed by Bob Giraldi. Bob said he remembers it being extremely cold that day when you shot at the bridge.

It was freezing cold, and we had the oil cans burning like the homeless guys under the bridge. Bob was at the peak of his powers directing TV commercials in New York. He was great to work with, a real pro.

If you go online, you can see some of your rare early videos, like “Portable Radio” and “Wait For Me” from your 1979 album X-Static.

Yes, but we did those on our own. Here again, they preceded MTV. Green screen had just become available, and there was a guy who was a friend of my sister, and her son was a film student, and he presented us with the idea that he could put us in any environment we wanted using that green screen. So we shot those, and that giant wine bottle. And the boom box, which was the hip thing of the moment, gave us the idea of, why not shoot it like we are performing in a giant boom box? Here again, that was pretty adventurous for the time.

DARYL HALL & JOHN OATES【WAIT FOR ME】1979 by xxxTitanheadroomXXX

I have to ask about the infamous “She’s Gone” video, the one with you and Daryl sitting in chairs with all kinds of trippy things happening around you.

Oh. Well, that’s the best video we’ve ever done. (laughs) That was way before videos were the norm. That preceded MTV by eight years or so — 1973 or 1974 I believe. There was a kids dance show called “Summertime at the Pier,” a teenage dance show in Atlantic City, NJ. Every Saturday, it was a TV show, and there was a DJ. He would spin records and the kids would dance, similar to American Bandstand, except that it was a local Philadelphia show in the afternoon. So the record company wants us on this teenage dance show, and we said, “We can’t sing ‘She’s Gone’, a ballad, on a teenage dance show! The kids will just stand there and look at us like we’re nuts!” They thought we’d just show up in suits and lip sync this song. We told them we couldn’t, so they said, “Would you come to the local TV station and record something for the show that would be inserted?” And we said, “Yeah, sure.” So we’re sitting in New York thinking about it, and we decide to do something that just blows their minds. For this video, we literally took the two chairs from our living room since Daryl and I were roommates at the time, we had Sara [the inspiration for “Sara’s Smile”] as the girl, the devil was our tour manager at the time Randy Hoffman, I rented a penguin suit, Daryl had his bathrobe, we brought Monopoly money, and we did this crazy little play.

My sister, Diane Oates, who was a film student at Temple University at the time, directed it. She’s still a producer today for ABC-TV in New York. The people at the studio looked at us like we were nuts. They were in shock, and they kind of let us do it reluctantly, with a lot of grumbling in the background, and then the show never aired it. They thought it was so outrageous that they wouldn’t put it on the air. The TV station actually tried to get us banned from Philadelphia radio! They said, we don’t know what these guys are on, but they’re crazy, and no one should play their record now. I think it’s one of the greatest things we’ve ever done!

Check out everything Hall & Oates on their website, and John Oates’ compilation “Good Road To Follow” is available everywhere.