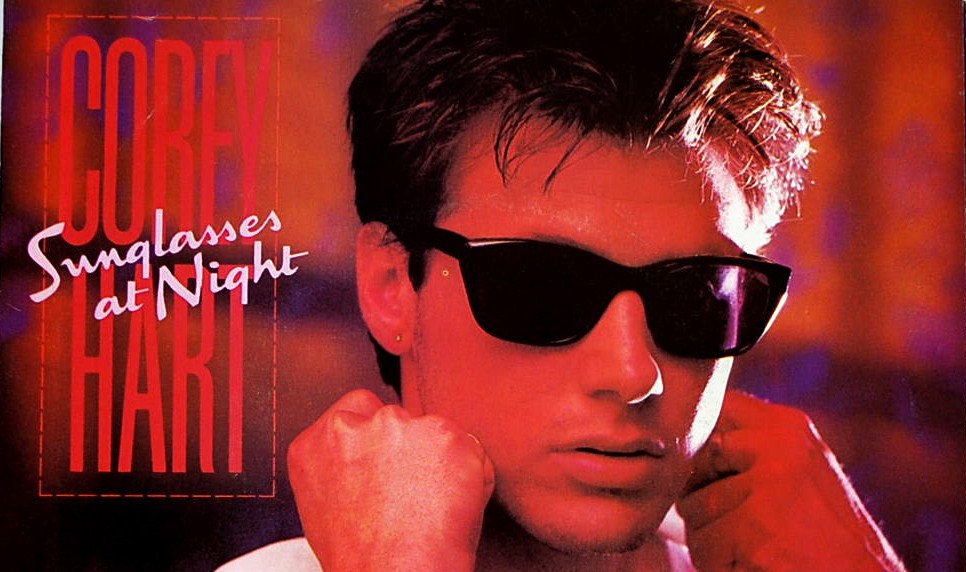

Don’t Push The Blade On A Guy In Shades: “Sunglasses At Night” Singer Corey Hart Remembers His Classic Music Videos

The rock world has seen its fair share of Canadian rockers, from Rush to Bryan Adams to Glass Tiger, and in 1984, all eyes were glued on a guy named Corey Hart and his single “Sunglasses at Night”.

With a Billboard Top Ten hit right out of the gate with “Sunglasses”, Hart sported a pouting mug and songwriting talents, eventually selling over 16 million records worldwide and scoring nine consecutive US Billboard Top 40 hits (in Canada, he is even bigger, with 30 Top 40 hits, including 11 in the Top 10, over the course of his nearly 30 years in music). A Grammy-nominated singer of hits such as “Never Surrender”, “Eurasian Eyes”, “Boy in the Box” and a gentle remake of Elvis Presley’s “Can’t Help Falling In Love”, Hart reemerged on the charts in 2012 with Canadian DJ 1Love on a remix of the song “Truth Will Set You Free” from his YOUNG MAN RUNNING album. Recently, “Sunglasses at Night” has resurfaced, with Hart’s participation, in a hybrid remake/mashup called “Night Visions”, featuring Hart teaming with Chicago-based DJ production team Papercha$er.

We spoke with Corey Hart about his memories of the videos that put him on the map.

GAMV: Let’s start back at the beginning.

Corey Hart: Where is the beginning? (laugh)

Let’s start at a pivotal moment, with “Sunglasses at Night” back in 1982, when you were writing the song, did you have some stark visuals in mind?

When I was writing this song, my record was pretty much finished. I came back from England and wrote it and went back. Did I say that I had visuals in mind in an interview before?

I believe so.

Well, it’s possible! I may have had that in my head as a twenty-four year old, I don’t know. I can’t exactly remember, and I’ve got a granite-like memory. Ten years from now I’ll remember this, but…I wasn’t visualizing the video when I wrote it, but he minute I knew we were going to shoot it, I started thinking of visuals for it.

Was the original content of the song more political? The director, Rob Quartly, said he thinks it may have been.

I recently spoke to Rob, and we hadn’t talked to him in a while. I have the greatest respect for Rob, and in fact, he’d invested a lot of money from his own company in that video. He financed it in part because the record company was only going to go so far with it, and the concept required a little bit more.

Was it only on Aquarius Records at that time?

Yes, I felt so fortunate to be signed to Aquarius at that time, and because videos were so powerful at that time, so there was no doubt in my mind as an artist debuting on the music scene that I needed a video. Rob was one of the premier video directors in Canada at the time, and long story short, he really went to bat for me, and was the perfect “first time” director for me – not his first time, but mine. I couldn’t have asked for a more appropriate choice. I think the political idea you mentioned may have been our “1984-George-Orwell-Big-Brother-Is-Watching-You” theme within the video, but truthfully, I wasn’t writing about that in the song.

What do you recall from shooting at the Don Jail in Canada?

I have a lot of memories. I was really nervous because I wasn’t sure how I was going to project onscreen. I’d never seen myself before onscreen. Normally, as the medium developed, you’d have instant playback, but we didn’t. I do remember on the first scene we shot where I’m sitting at the table, I move my arm to grab the shades on the beat. I’m sitting in the Don Jail, they were fixing the lights and said, “we’ll have a stand-in sit there for you for now,” and I said, “No,” because I wanted to do everything I’m supposed to do, A to Z, to make it authentic. I must have stayed in that slumped position, which you see at the beginning, for about 50 minutes. That’s not good for your spine or back or arm, and I didn’t move because I didn’t want to mess them up when they were lighting that scene. My arm fell asleep, it went numb. Rob’s like, what’s wrong? (laughs) I remember that a lot of people who worked on the video kept telling me it was going to be a hit. I was a kid, so I was excited that the people working on the video actually enjoyed the song, or so they said. (laughs)

Laurie Brown of Much Music is in there as the prison guard.

Yes, Laurie was in two of my videos.

In the scene in the phone booth, that was shot with faster film and slowed down to match the song, so you had to sing it at twice the speed (similar to the Police’s “Wrapped Around Your Finger” video). Because there was no pitch correction at the time, it must have sound like a chipmunk version.

Sure, it did. When I lip-synch I don’t mime, so I sing live. I do vocal sync. You know, I must have seen that video a zillion times, but I do a little blink when I leave the phone booth that I wish I hadn’t done. A minute detail.

I wanted to ask you a few more about some other videos. You worked with director Meiert Avis on some other clips.

We did four. The most beautiful ones he shot are the latest one and “In Your Soul”, which strangely enough, precedes “Truth Will Set You Free” on that album. We did the last one in 1994, in Paris, for “Hymn To Love”, shot beautifully by Meiert, as they all are.

I was noticing that in many of your videos, your visual sense seems to connect you to a rebel, a man alone, a struggling character. You can’t get much more rebellious that your James Dean-type in “I Am By Your Side”.

My one acting line, eh? (laugh) Have you seen the full video? You hit it on the head. When I first started out, people did say James Dean, and also when we did the video. There’s an intensity to me when I’m performing, not so much Ricky Nelson-ish, you know? I am not of that cut, Donny Osmond, or something like that, but funny enough, I’m not a brooding type. You know, “Boy in the Box”, was actually written about James Dean.

Speaking of “Boy in the Box”, that one had a larger scope, and falls into that video style that references films like Big Trouble in Little China –

More like Blade Runner, I thought.

Yes, Blade Runner! I can see that now.

The director was very creative and flamboyant, Michael Oblowitz, a South African. Very mercurial. Inspiration would hit him, he’d move left, he’d move right, and he moved through things very quickly. We had a bigger budget. We had achieved some success with the singles so we were able to expand. We had great stage production and art direction on that one, costumes and cinematography. It’s got a few people in there, such as the producer on my first two records, Phil Chapman, and Steve Anthony, the DJ who used the phrase “the Boy in the Box” on the air. He didn’t originate that though. The first guy to say that was from Chicago, WLS, John Landecker. Steve Anthony ended up being a VJ on Much Music.

When it comes to a large production like that, what do you recall?

More elaborate casting and costumes, we built it all on a soundstage. It had a real Duran Duran “Wild Boys” feel to it. That and Blade Runner were our visual influences for that. My kids ask me why the Chinese barber was wanting to cut my hair, and I always say, “I have no idea, darling.”

“Eurasian Eyes” looked like a cold shoot.

Well, I told Rob that I couldn’t ride horses! I told him that I hadn’t been on a horse since I was five, when I lived in Spain. But the minute I got on it, I thought, holy sh*t, this horse is going to kill me! It doesn’t like me! So in the scene where I’m walking the horse, you can kind of tell it doesn’t like me because its ears are pinned back, and that’s usually an indicator that the horse isn’t feeling the love, and it wasn’t from me. I’m obviously not a horse guy!

On “Never Surrender,” that was a huge song for you, and it’s become sort of a theme for folks. The video seems very faithful to the song. Did you and Rob collaborate on the story for that one?

Rob and I always did that, as with all directors. I’m a singer songwriter, so the visuals that accompany my music are going to have my imprint on it. I’m not going to just show up at a video shoot and have the director say, hey, here’s what you’re going to do. I couldn’t work that way. There was no question that Rob was going to direct this because it was the first single off the second record, and Rob had done the two off the first and got me there. It is true to the lyric, it follows the narrative. It’s pretty simple really – leaving home and wandering the streets, hitching a ride, getting thrown out of a diner, and playing this club, a very famous Toronto landmark for musicians called the Rel Mocambo. I think the Stones did a live record there once. When I get pushed out of the diner by the owner, that’s next to the club. And that scene in the rain? I’m really shivering.

That scene in the hotel where you sit down and just put your head in your hands. We usually see you very strong and determined, but in that moment, it seems like you are about to break down.

I think that anyone who really knows my material, and not just a snapshot of it, would know that I’m a really sensitive person. As much fortitude and inner strength that comes from me, there’s also a lot of vulnerability and a lot of tenderness. I’m definitely both sides, so that scene where I put my face in my hands, I feel like the world has just abandoned me, and I don’t know where I’m going next. It was appropriate — not giving in, but being emotional. I am emotional for the better and the worse.

“Never Surrender” seems to have really hit a chord with people. Did you think that would happen when you wrote it?

I never imagined it would have such an impact on so many people, to the point where I have received thousands of letters over the course of my career about how that song, say, saved someone from suicide and made them rethink their dilemma. Of course it’s a song, and it can’t be a cure, but so much of what we draw from as individuals, whether it’s a movie or a book or a song or a painting or even a landscape, we can draw strength and inspiration from those things, and we can even perhaps settle some of our demons. To answer your question, I hoped as a kid that my songs would touch people, and they would move people, because that’s all I wanted to do. Make them think and make them feel. From a moment of just sitting down at the piano one night, it was born, and the fact that it touched so many people is the greatest gift a songwriter can receive. I’m very grateful.

Catch up with Corey Hart at his website CoreyHart.com