As R.E.M. Says Goodbye, Director Peter Care Recalls Shooting The Music Video For “Drive”

After thirty one years of making music together, the members of the band known as R.E.M. announced earlier this week that they were calling it quits. A uniquely singular band that ascended from their position as college rock darlings to mega-platinum mainstream conquerors, R.E.M. enjoyed the sort of evergreen critical acceptance rarely seen in pop music. The band created over sixty music videos over the course of their career, with images that serve perfectly as career snapshots for the group from Athens, Ga.: the head-phoned, shaggy pleading in “South Central Rain”, the firecrackers and disjointed faces of “The One I Love”, the fallen angels and falling milk pitchers in “Losing My Religion”, the highway wanderers of noir in “Man on the Moon”, the despondent drivers in “Everybody Hurts”, the wiggle dance of “What’s the Frequency, Kenneth”, the visual rollback of “Imitation of Life”, and so many more (we’ll forgive and forget “Shiny Happy People” for now).

So as we bid the band farewell, THE GOLDEN AGE OF MUSIC VIDEO has chosen to concentrate on the music video for “Drive,” an ethereal dreamlike clip shot in black and white with a crowd of fans at the Sepulveda Dam in Los Angeles in August of 1992. Director Peter Care, whose cinematic sensibility gave rise to expansive clips for Cabaret Voltaire, Depeche Mode and others, began working with the band on Out of Time’s “Radio Song”, but he pulled out all the stops for the lead-off single for possibly their greatest major label effort, Automatic for the People. We spoke with him about the creation of this epic clip.

I think part of what makes “Drive” work is that, as with a lot of your music videos, we’re off-balance.

Yes, absolutely. Well, with Michael [Stipe] at that point, we had a pretty good relationship, very trustworthy, if you like. I thought he was pushing the arrangement where we could actually tell each other if their ideas sucked or not. You can’t really say to musicians or pop stars, “I’m not going to do that, the idea sucks,” because you wouldn’t be there in the first place. So for Michael and myself, he said he wanted to do black and white, and I said, “Yeah. Okay, cool.” He said, “And I want it to be an homage to crowd surfing. I want it to be the greatest crowd surfing music video of all time and then I’ll never going to do it again,” and then I’m,” Okay, cool.” And he said, “I want to do little bits that look a bit like Civil Rights moments, but instead of pointing of water hose at poor African-American people, you’re going to point it at each member of the band and they’re going to get soaked.” I said, “Okay, sounds good.” He said, “Look, I don’t want to sing the song perfectly in synch. I’m going to leave out words.” I said, “Okay, great, and I’ll shoot it at the wrong speed so it’ll never be in synch ever,” and he said, “Okay, that sounds great.” And then he said, “And then I want to do–I’m thinking of being naked from the waist up, you know. I’m going to shave my chest and I’m going to be naked,” and then I kind of winced a bit and he said, “What’s the matter?” I said, “Well, I thought I could work–I don’t know if it’s going to look a little bit too like a–a little bit too vain or you’re trying to look like the next year’s Iggy Pop or something. I think that if you kept the shirt on, and the shirt got wet, it could look kind of more poetic or something.” I don’t know what I said. Rightly or wrongly I’ve decided to keep the shirt on. And all of this happened of organically. It just kind evolved.

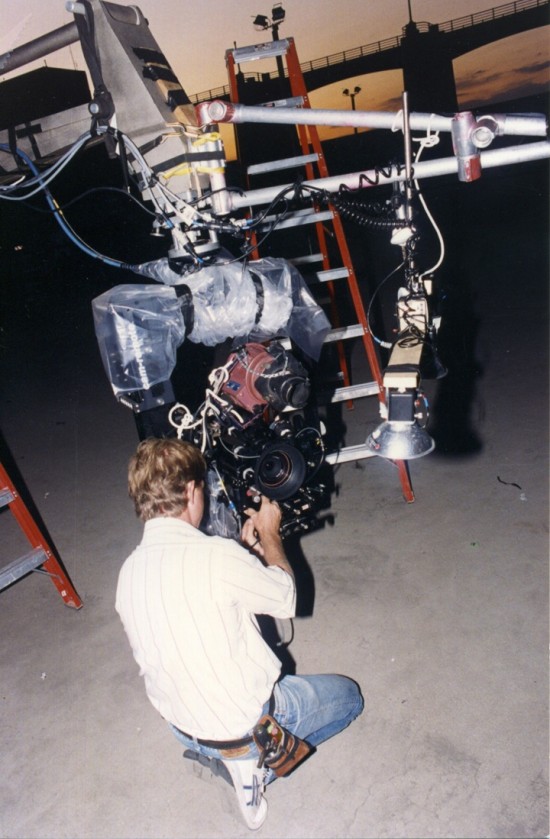

on set photo, courtesy of Peter Care

The image that I always had in my head was a very famous painting by an artist called Delacroix of people that–there’s like these people on a raft and they’re in a storm and people like kept falling off the raft.* Now, here’s the thing. I never looked at that painting when I went to do the “Drive” video. It wasn’t in the forefront of my mind that, “Oh, here’s the painting. I’m going to copy it.” But the image of Michael Stipe on a sea of hands under a strobe light would to me felt like he was a sailor in a storm. It had that kind of like early 20th century romance about it, and that’s why I didn’t want him to look like a pop star without a shirt, I want him to look like a poet in a storm or something. But if I’d have shown that to him he probably would’ve laughed or something. It inspired me anyway, probably…I don’t know.

[*Care may be referencing either Delacroix’s Christ on the Sea of Galilee or The Barque of Dante, but he may also be remembering Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa, which was an influence on Delacroix, and in a strange bit of coincidence, a painting that Delacroix modeled for as a favor to Géricault. He can be seen as the figure in the foreground with face turned downward and one arm outstretched. All three are included here.]

Christ on the Sea of Galilee, Delacroix

The Barque of Dante, Delacroix

The Raft of the Medusa, Géricault

You adjust the shots in these different ways, and you seem to get closer and closer to the tone and the heart and the sound of the song. You made changes in the speed of the film, and the flashing strobe light, and it’s almost like there’s a man on a raft in the water who is floating away, and there’s a ship passing by that has a light shining on the crowd, trying to find him.

That’s funny because no one has ever I mentioned that to me.

It’s a sea of hands and it’s a sea of people and that light going by was absolutely almost like a searchlight coming on, like you were trying to find him.

You know, that’s really why I’ve enjoyed working with R.E.M. and Cabaret Voltaire in particular. These people give me a brief and sometimes I kind of purposely ignore the brief in little instances, like for instance for that, Michael, wanted the strobing to be really hard-edged. In other words, when the strobe was off, the frame would be black. And I said to him, “Well, I’ll shoot a bit like that, but Michael, I’ve kind of done it, and it’s not as pleasing. What if you have something in the frame that is constant and the strobing again becomes more hypnotic and less like a ‘rock and roll’ strobe. And he’s like, “Well, okay.” So when we put the camera upon the crane to look down on the crowd, it had this little spotlight and it’s always on. But there’s never a black–completely black — frame. In fact, that shot—we did some takes like that. I didn’t like it and Michael never asked me to include them, so I think of it as if a kind of instinct. You give the audience or the human eye something to latch onto in the middle of what could be total chaos. I always wanted to feel like there’s something unexpected, because, let’s face it, lots of people have done music videos based on just strobes, a lot of strobes and flashes, and so on. I wanted it to be…

You wanted it to mean something.

Yes, and you wouldn’t lose sense of Michael. That was such a great shoot and I was really proud that I operated the remote camera myself. When you have training and you have these kind of like wheels that can pan the camera but pan it and tilt it and so on, and they have adjustable gears, so you can have really kind of wrenched solid so every simple moves you make with the camera reflects or you can have them really loose so that the camera can never really catch up with the instructions you’re giving it mechanically and that’s what I set it on, I set it on a really loose settings so that I knew that I would always be half a beat behind Michael. Wherever the kids take him, my camera would never be set up to get it. It would always have to find him, and that was really great. I was sweating like a pig after about an hour. I don’t know, I just had a lot of fun.

on set photo, courtesy of Peter Care

on set photo, courtesy of Peter Care

I think part of what makes you feel off balance is that the crowd is moving, and Michael is moving, but the camera is moving, and because the camera is moving, you don’t have a full sense of equilibrium.

I tell you, there were two instances that I was really proud of with that music video. One was when I showed the first cut to Michael in a little viewing theater. And I’ve got to say kudos to the editor whose named Robert, and he cut it together beautifully and amazingly and I remember Michael coming in to see it, which was unusual because normally they did everything together, as a the band, the four of them would always do this together. It wasn’t the Michael Stipe Show, by any means. But anyway, he was the only one in LA at that time. He came in, he sat down, we watched the video and the lights came up and it’s that classic moment of absolute silence, and I’m thinking, “aw f*ck, he’s not liking it, f*ck. He hates the shirt.” And there’s silence and he just put out a huge sigh and he’s sort of like, “Ooh”, and he said, “That’s just incredible. Can I watch it again?” And then that was it, we never cut the frame after that.

Wow!

That was a great moment. That was a very great moment. And the other time –the other thing about video is that because there’s quite some show a few years ago and some people shown my work with some other directors, they showed it on the big screen, and it works incredibly well, I must say, on a big cinema screen…

Oh, man.

…yes, I’m so proud of it. I wish it could happen more. I wish there were more outlets to show like classic music videos big because I’m telling you that it’s incredible when you have that sea of people and the strobe lights hitting you on a massive scale. It’s really incredible, actually. It’s one of my favorite videos of all time.