Thriller director John Landis talks movie monsters, music videos and, of course, Michael

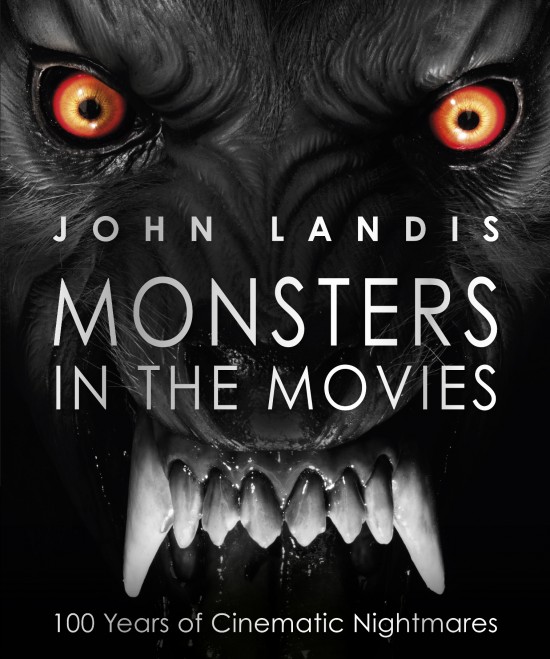

When John Landis got a call from Michael Jackson in 1983 saying he wanted to turn into a monster, it would forever push the boundaries of what a music video could be. Michael had famously seen Landis’ film An American Werewolf in London and was inspired seek out Landis to helm Thriller, possibly the most famous music video ever made. But Landis’ love of monsters is lifelong, having started as a kid watching monster movies on TV, and having directed his first film Shlock, a monster picture. Now in 2011, Landis has written a fantastic book called Monsters in the Movies, filled with painstakingly compiled data, insightful director interviews and vivid monster movie photos spanning 100 years of creature feature history.

Landis took a moment to speak with THE GOLDEN AGE OF MUSIC VIDEO about the new book, memories of Thriller, and much more.

(May 2020 update: All the questions and answers about Monsters in the Movies appear here, but the Q&A about music video has only been excerpted for publication here; an expanded version will appear in the forthcoming MUSIC VIDEO TIME MACHINE magazine)

**************************************************************************

GAMV: The book is a wonderful collection.

John Landis: I’m a lifetime fan of monsters and fantasy.

Kids today don’t really understand the limited movie access people had when you were growing up. From the 1980s onward, between rentals and today’s on-demand everything, you can get every movie ever made now, but it wasn’t always that way.

You know what’s odd, though? You’re quite right, but I find that kids today seem to have no knowledge of old movies at all. It’s quite shocking, because it is available.

Your love of monsters in cinema began where?

Probably when I saw the old Universal classics on television as a kid. Universal Studios packaged all their old movies in syndication to Shock Theater, and so when I was a kid I used to watch all the Frankenstein pictures and The Mummy and The Wolfman and Creature from the Black Lagoon, and movies like that on TV. I grew up in Los Angeles and there was an RKO station, Channel 9 – they had one in New York, too. I don’t know the station, but it was the Million Dollar Movie, where they would show the same movie every night at eight o’clock, and then four times on the weekend. I saw pictures like Godzilla and Mighty Joe Young ad infinitum. I could memorize them.

All the filmmakers you interview in the book you’ve known for a long time. Throughout your career, you’ve had many directors do cameos in your films as well. Do all monster movie filmmakers have one personality trait in common?

They tend to be very nice guys. (laugh) I’m very serious! They tend to be very sweet, very gentle, very funny guys. Most of them have a really good sense of humor.

What do you attribute the return to vampires and zombies in popular culture and film lately? What keeps people fascinated about those monsters? You touch on this in the book, that zombies are a comment on the aging of western culture.

Zombies seem to be the monster of the twenty-first century. As Joe Dante says in the book, “All monsters are metaphors.” His example he gives is Godzilla, where you have a country, Japan, literally the only country in the world to ever have an atomic weapon dropped on it, and shortly thereafter they make a movie with this giant prehistoric dragon-type monster that’s radioactive and lays waste to cities. It’s pretty obvious , but you trace the history of post-war Japan through the Godzilla pictures, it’s really interesting. He becomes the protector of Japan, the good guy. It really depends on the zeitgeist, but zombies, as David Cronenberg points out, are us. I mean, that’s what we will become, in terms of a metaphor for old age and decrepitude. But even to be more obvious, as agents of the apocalypse, which is what they are being used for now, is to represent anarchy and the collapse of social order, which is clearly what is happening all around the world. (laugh) I really think that is the thing behind the popularity of the zombie at the moment.

Throughout your research for this book, which monster’s background was the most surprising?

Well, I learned lots. The conclusion that I came to is that monsters are very clear representations of mankind’s fears — and aspirations, by the way. It’s clear that as a specie, as hairless monkeys, we cannot tolerate not knowing things. For example, death. Death is something that don’t really know. We get it physically, but nobody knows what it’s like to be dead. What really happens. So what we do as a specie is invent. We create philosophies and religions and zombies and ghosts. And vampires and all kinds of walking dead. Historically, who is the first zombie? The first one I could find was Lazarus. And there’s an argument to be made for Christ being a zombie too. It’s people who come back from the dead. It’s the living dead, and it’s a very common theme throughout international culture, not just western culture. Monsters seem to be necessary for us, from primitive cave paintings to the most sophisticated computer generated imagery, we’re still just making monsters.

What are some monsters films that most people don’t know that they should seek out?

There’s a brand new Criterion Blu-Ray DVD of one of my favorite monster movies, which is called The Island of Lost Souls. And it’s gorgeous. They really went to a lot of trouble to restore it. It’s a picture made in 1932 or 1933 by Paramount, right after they did their very beautiful Jekyll & Hyde with Frederic March, a [director Rouben] Mamoulian picture. Both were Paramount, and both are well worth seeing. It was an unusual situation in the case of Frederic March actually winning the best actor Oscar for portraying a monster, and his Hyde is really monstrous, becoming more and more apelike every time he changes. They’re both pre-Hays Code pictures, so they are very upfront in their violence and sexuality, and quite remarkable movies, both of them. I really recommend them. Have you ever seen Freaks?

Yes, Freaks is unsettling.

Well, it’s so interesting. I didn’t realize that Todd Browning came from a circus sideshow background, and was very familiar with freaks as friends and childhood companions growing up. He is an interesting guy. I mean, his pictures with Lon Chaney and Joan Crawford, the one where Lon Chaney plays the guy with no arms who really has arms [The Unknown]? It’s the most bizarre movie in which his rival for Joan Crawford’s affection ends up tying him to these horses to rip his arms out. I mean, it’s unbelievable. Browning is a fascinating guy.

How do you feel about Suspiria and some of the more bizarre films like that?

You know, Suspiria was a actually a big success in the United States commercially. It played all over the place. It started as grindhouse and word of mouth made it quite a successful picture. Here’s a bit of trivia – do you know when I first met Dario Argento? I was a stunt guy on Once Upon A Time in the West, a Sergio Leone picture made in Almeria, Spain. He shot in the United States, too, but I wasn’t in the American part, just in the Spanish part. The two writers, these two young film critics, were on the set, very excited and enthusiastic, and they were Bernardo Bertolucci and Dario Argento.

And you just kept up with each other over the years?

Yes, Dario especially.

Some say that comedy and horror work differently from drama because you know right away if you’re getting it right – in comedy, you get the laugh and in horror, you get the scream. In drama, you don’t really know if you are getting it right away. Would you agree with that?

Not entirely, although they are on the right track because when I’m sitting in a movie theater, I know if a movie is working or not. (laugh) But what is true is that both comedy and horror are unforgiving. It’s either funny or it’s not, it’s either scary or it’s not. Very unforgiving genres. Also, they are both physical. You have a spastic response – you either gasp or laugh. These are explosive physical responses. They’re very similar, actually.

One thing I was really glad to see in the book was the mention of the Anthony Hopkins film Magic. I am a child of the seventies, and just the commercial of that film gave me and many kids I knew nightmares for weeks. I read that they had to take the commercial off the air.

My son Max, who is a screenwriter, is now twenty six, but when he was a little boy, he came to my office at Universal and he saw the Child’s Play poster with Chucky. It horrified him and he had nightmares for weeks. There’s something about those dolls, those inanimate objects that are really creepy. Have you ever seen a British movie called Dead of Night? It’s a portmanteau film, an anthology film, made during the war by Ealing. Four directors, and it’s brilliant. That would be one of my top recommendations. It’s four or five stories held together by a genius connecting story that I don’t want to say anything about because it’s so smart. It’s a wonderful film and genuinely creepy. There’s a dummy sequence with Michael Redgrave – there’s a photo of it right next to Magic in the book – that’s the one that everyone takes from. The Twilight Zone, Magic – everyone’s stolen from that. Michael Redgrave is brilliant, and there is a moment that I don’t want to spoil that is so remarkable. The film has four or five stories and one of them stars these two British comics of the forties, and that’s the only unsuccessful one because it’s very English and very forties, and it’s a forced kind of humor that a lot of Americans don’t get. Other than that one segment, the movie is dazzling. It’s got the best ghost story, oh, and you know what else comes from that movie? “Room For One More”, a wonderful sequence where a guy is rushing for a bus, and he’s just about to get on when the conductor turns, and the conductor is this kind of creepy guy who says “Room For One More?” and the guy is so taken aback by how creepy the conductor is that he steps back. He doesn’t get on the bus, and then the bus goes and gets into this gigantic crash. And then I won’t tell you what happens next. Those are three movies you’ll thank me for.

Here are just a few excerpts of Landis’s comments on his music videos. The full interview will appear in its full form at a later date.

On Thriller’s dance sequence:

The best filmed dance sequences I’ve ever seen are still in the Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers movies with Mark Sandrich where he would do these elaborate crane shots, but hold them head to toe together because these people could really dance. When you have all the fast cutting and stuff in a movie like Chicago, it’s because Richard Gere can’t dance, and so you have to cut like crazy to give the illusion. But Michael was a brilliant dancer, and I realized that I had an opportunity. In The Blues Brothers, because John and Danny were not professional dancers, I used only amateurs in the dance numbers, and then lived to regret it when I came back to L.A. to finish the movie. The only number that does have professional dancers is the James Brown number in the church, which is one of the last we shot. So, I love musicals, and that’s really why I said yes to Michael, because I thought, great, I can make a little musical here.

On getting to work with Vincent Prince for Thriller:

I had hoped to use his track from the record, but it was mixed in with a synth track, and I needed to isolate it for my mix. I called Vincent Price and I asked him if he would come in and he graciously came in. He did it in fifteen minutes, he just read it. I knew him, but we hadn’t worked together. It was the one time I ever worked with him, and he was delightful. I mean, he just did it so quickly. And then we went to lunch at Musso and Frank and I listened to stories.

On how he came to shoot Michael Jackson’s “Black or White”:

Propaganda had made a deal with Sony to produce all the videos for the Dangerous album. And they were in big trouble. They’d already spent a fortune and hadn’t produced anything, and Michael wasn’t showing up. Basically, they called me because they knew that Michael would show up if I was there. Which was true. So I called him and said, “Michael, the only way I’ll do this is if you show up.” And he said, “Yes I will,” and “Don’t worry.” I mean, they had David Fincher, David Lynch, a lot of really good directors were burned through before I got there. They just couldn’t accomplish anything. I said, “I’ll do this, but you’re paying me on a weekly basis.” (laugh) I actually did a wonderful tap dance sequence with him that Michael then didn’t use. By that time, I was saying, “Mike, you’re such a great dancer,” but he insisted on doing the same twelve moves everyone loved. He could really tap, so we did a wonderful tap dance number. The only thing left of it in the video is you see him do two steps and then kick a bottle in slow motion.

On the speculation that Thriller will be remastered digitally for a 3D release:

That may happen! That depends. I’m still in my lawsuit with the Jackson estate. That’s being resolved. You have to do [a full restoration of the original film] before you can transfer it to 3D. There’s no obstacle, it’s just the estate. The estate is involved in a lawsuit with me. It’s very straightforward issue – they owe me money and they don’t want to give it to me. They will. I’ve gotten some money already.

On being asked to direct music videos after Thriller:

I got asked a lot, but I never really got into the rock videos because the way the business formed. I don’t know if you know how it worked, even in the heyday of rock videos, but what would happen is the act or the label would send twenty five different people the record – all these production companies. They say, “Here’s the song, we want you and the director to come up with a concept — which meant very elaborate storyboards and basically, the video – and we want you to pitch it to us with a price.” They’d get fifteen or twenty presentations, and they would pick and choose, and I thought, “Fuck that.” If you want me to do that, hire me. I’m certainly not going to audition, and I’m certainly not going to write it for free. (laugh) So I never got into the rock videos because that’s what directors had to do. For quite a while there, it was big business. Lots of groups [approached me], but they wanted to go through that process. Aerosmith, Duran Duran, all those guys. That was in the eighties. Many many groups approached me, but they’d want me to do the work up front, and I said, “I’d be thrilled to do it if you hire me, but I’m not going to audition for you.” (laugh)

On shooting the Paul McCartney video for a tie-in with his film SPIES LIKE US:

So we shot stuff, and there was some funny stuff at Abbey Road, with Danny and Chevy playing instruments and stuff. Then it turns out that there’s a British union rule that you cannot play an instrument on film unless you’re a member of the musicians’ union and can really play it, which is crazy. So I couldn’t use any of that, which was most of what I shot. And then I said to Paul and Linda, who owned it, “you finish it,” and they did. I don’t think the video is very interesting. I did get the walking-across-Abbey-Road moment, and also there’s a moment with a guy in a Prince Charles mask who takes it off and it’s Paul. As for the video, I was tricked into that. I mean, I like Paul. He’s very nice. But it was kind of a weird situation.

On MTV rejecting the two B.B. King music videos he shot as tie-ins to his film INTO THE NIGHT:

MTV refused them, basically because B.B. was too black and too old. A junior person at the network told me that. I mean, they didn’t give me a reason, but that’s the reason. I have something with Steve Martin, Eddie Murphy, Danny Ackroyd, Michelle Pfeiffer, and they wouldn’t play it. It turned out to be a half-hour program, once you cut together the [B.B. King] documentary and the videos and stuff. It was given to Black Entertainment Television, and they basically played it four times a day for three years. (laugh)